Reflections on the Adoption and Use of Obstacle Boards in Agile Practice

Life is full of obstacles. Be it school, work, home or any other feat we set our sights on, there’s bound to be a few blockers along the way. Let’s be honest, if every desire or achievement came easily, life would be rather dull and unfulfilling. While we can’t always get what we want, jumping a few hurdles builds us up better than having everything handed to us on a silver platter.

Software development is no different to life. Regardless of the process and technologies utilised, teams will encounter issues. My personal view is remediation of these blockers make building software to be one of the most challenging and fulfilling pursuits. There is nothing more satisfying that solving an issue that has been plaguing your progress. However, in order to achieve that dizzying high, we must first identify and remove the obstruction.

Recent challenges with development of a new product have required some experimentation in how we manage impediments. Our latest experiment is using an Obstacle Board to visualise and track problems. While I’ve found many useful resources describing what Obstacle Boards are, and how to create them in particular tools, people’s experiences of using them seem to be less forthcoming. This week I ponder the successes and challenges of our recent Obstacle Board adoption along with next steps in our journey.

Outside the Wall

While there are many resources that describe what an Obstacle Board is, a brief overview is definitely required. I have certainly found that almost everyone has some knowledge of Scrum and Kanban boards, but that same population are less familiar with Obstacle Boards.

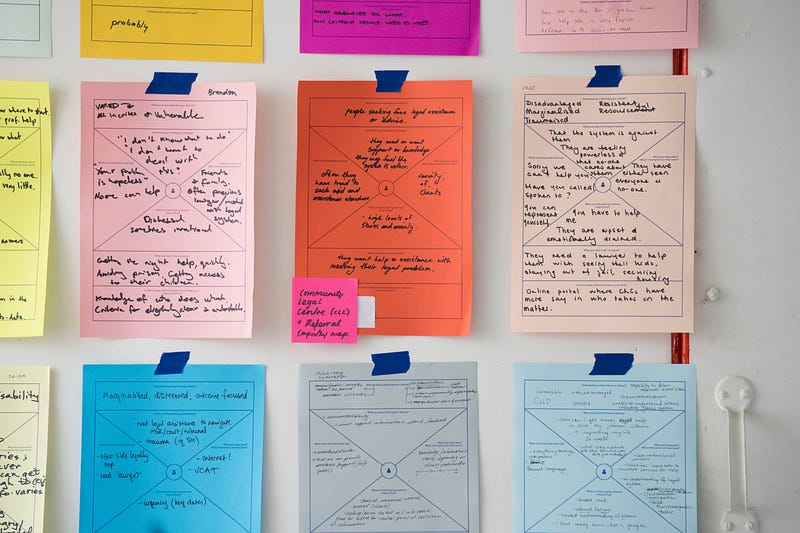

Quite simply, it’s a twist on the usual story board that the majority of Scrum and Kanban teams use. Regardless of whether you use physical boards and post-its, or tooling such as Jira and Trello, an Obstacle Board provides visibility to the state of any impediments to your current work. As pictured below, blockers can still go through a simple workflow to address them, or even be integrated into your existing Kanban Board as discussed by Judicael Paquet.

Before adding an Obstacle Board to our process, it was important to provide an education to both developers, business analysts and the product owner. Not only is this required to explain the concept, it can help to justify why it should be introduced, and facilitate discussion on if and how the team would like to use this technique. In particular, I have found the following resources useful not only in reinforcing my own understanding, but also in this education exercise.

- Obstacle, Begone! – Aaron Sanders, This Agile Guy

- Obstacle Boards in Agile? – Judicael Paquet, My Agile Partner

- Visualise Problems With a Board – Johanna Rothman, Create Your Successful Agile Project

Building a Wall

Now having done your homework, you should know the purpose of an Obstacle Board. The next question on everyone’s lips is normally what is an obstacle? This is an interesting idea in itself as engineers perceive a blocker to be an issue that means they are not able to make any progress on an item. Snags that slow them down are not considered to be impediments as they are still advancing to their goal. A common understanding of what constitutes a blocker also needs to be agreed when adopting Obstacle Boards.

Our key problem here was stories were not being completed in the sprint due to logic investigations. With the build out of the new product, comparisons against the existing legacy system found behavioural differences. These proved to be a significant challenge for the development team, who needed to identify the root cause of these differences. Initial tracking measures attempted by the business analysts included Excel spreadsheets and email threads.

The team encountered several issues with reacting to these notification mechanisms. Firstly, the Excel sheet revisions being sent out daily resulted in many duplicate items when the same issue was encountered. The development team struggled to identify key themes, which made raising of defects to fix difficult.

Furthermore, investigation progress was all but invisible as we could not identify when issues were being investigated, and by whom. For those discrepancies that were investigated, significant delays were experienced as all updates were chased via email. Engineers don’t monitor their email constantly to reply to update requests, and if they did I wouldn’t certainly expect a reduced productivity rate as they’ll spend less time engrossed in their favourite IDE. These issues come under the latter definition of blocker, making them more impediments to team progress. Something had to be done.

Climbing Up the Walls

Like any experiment, control parameters and metrics needed to be set to allow for us to measure the effectiveness of the Obstacle Board. Firstly, we needed to identify the issues that were going to capture on the board, along with those responsible for raising the items. It was agreed to focus solely on the data integrity issues rather than raise other development blockers that programmers face while coding. Effectiveness was to be measured by tracking the number of obstacles raised per week, and time taken to commence investigation. Our hypothesis was that both would go down as issues were remediated and the tools accuracy improved.

I’m not going to quote numbers, which may sound strange given the push for quantitative metrics. I’m happy to reporting that both measures have been experiencing a downward trend. In fact, over the last month no new logic snags have been reported, which is a huge achievement.

From a more qualitative standpoint, the board has proven to be a success. Both the Product Owner and Business Analysts have commented that the state of any investigations is more transparent. Any blockers can be explicitly assigned to developers and then back to BAs or the PO if further work is required. The added bonus is that they can be easily converted into stories where development is required, or linked together in the event that pitfalls originate from the same root cause. Developers are also reaping the benefits as they are better able to manage these investigations with other tasks.

Off the Wall

These initial accomplishments are amazing. However we do have some challenges to face to improve and expand our usage. In the current squad, we’ve had to tweak our capacity to ensure we can balance blockers with committed stories. Velocity is starting to even out, but for future efforts we may need to revisit the balance depending on the restrictions raised.

Board overload is a concern raised by some other teams when expansion to other squads has been discussed. I’ve already seen some reluctance to adopt on the basis that we are introducing too many boards. Many managers profess to the desire to have one board to rule them all. Coveting a single precious board has been far too limiting in my experience. Different audiences want a different view of state, be it precise development steps or a more high level, is it ready to deploy yet. Therefore, it is limiting to dismiss using an obstacle board purely for this reason.

Future plans are focused on expanding out Obstacle Board usage to other squads. A similar use case in other squad has already lead to requests from another Business Analyst group to suggest using the board in another space. However, blanket enforcement across all squads should not be the goal. Mandating tools and techniques removes the flexibility and team empowerment that Agile adoption is meant to provide us. Use Obstacle Boards when they can provide a benefit. Do not adopt them as the one ring to rule all issues.

Thanks so much for reading about our Obstacle Board journey!